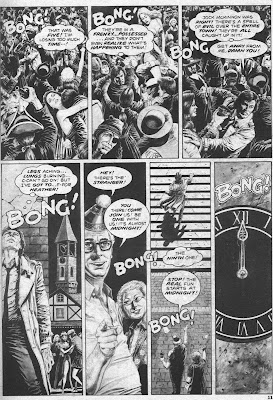

'Blood on Black Satin' episode three

by Doug Moench and Paul Gulacy

Episode Three (from Eerie #111, June 1980)

Here's the concluding installment of the series, scanned from the original magazine at 300 dpi.....

Monday, January 6, 2014

Friday, January 3, 2014

Heavy Metal January 1984

'Heavy Metal' magazine January 1984

One of the features in this January issue is a portfolio of pages from The Sentinel, a newly issued trade paperback of Arthur C. Clarke short stories and essays, with black and white illustrations by Lebbeus Woods.

The Sentinel, and succeeding volumes in the Berkeley Books 'SF Masterworks' series, was the brainchild of Byron Preiss, who was still resolutely trying to make graphic novels and illustrated books mainstream entries in sf and fantasy publishing.

While I can't say that Arthur C. Clarke is one of my favorite authors, the illustrations by Woods are very well done.

There are some good comics in this January issue; posted below is Segrelles's '1992', a sardonic look at the End of the World.

January, 1984, and the 80s are kicking into gear. On FM radio and MTV,

the latest single by The Fixx – ‘The Sign of Fire’ – is getting airplay.

The

latest issue of Heavy Metal magazine is on the stands, with a wraparound cover

by Mitch O’Connell.

By now - that is, the start of 1984 - , MTV was firmly in place as a pop culture

cornerstone, and even the most stylishly jaded of hipsters could not avoid

referencing it. So, the Dossier section hypes MTV, and provides a photo of

Robert Plant posing with the VeeJays – this picture communicates just how physically

tiny Martha Quinn actually was.

The Sentinel, and succeeding volumes in the Berkeley Books 'SF Masterworks' series, was the brainchild of Byron Preiss, who was still resolutely trying to make graphic novels and illustrated books mainstream entries in sf and fantasy publishing.

While I can't say that Arthur C. Clarke is one of my favorite authors, the illustrations by Woods are very well done.

There are some good comics in this January issue; posted below is Segrelles's '1992', a sardonic look at the End of the World.

Labels:

'Heavy Metal' January 1984

Wednesday, January 1, 2014

Book Review: Fugue for a Darkening Island

Book Review: 'Fugue for a Darkening Island' by Christopher Priest

2 / 5 Stars

Most Americans are unfamiliar with John Enoch Powell (1912 – 1998), a conservative British politician who in 1968 made a speech in which he predicted that immigration into the UK ultimately would lead to racial violence, as the native population found itself overwhelmed by the social and economic problems attendant to an influx of foreigners to a small territory.

The so-called ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech was denounced by the UK political establishment and the national media, and Powell was removed as a member of the Heath government. His name soon was promoted by the media and British intellectuals as synonymous with an element of UK society that embraced racism and bigotry.

Powell’s declaration touched a nerve among the working- and middle- class British population, however, and his attitudes towards immigration and cultural assimilation became subsumed into the larger issue of whether the British Isles had sufficient ecological capacity to support a large population. During the 70s, on into today, the increases in crime, crowding, depletion of the welfare system, and other social strains associated with immigration, maintained the middle class's sympathy for Powell’s stance.

As 2014 begins the UK Independence Party (UKIP), which calls for strict controls on immigration and the deportation of foreign-born criminals, has garnered unprecedented support at the polls, something which has greatly disturbed PM David Cameron and the Conservative party, the British political establishment, and the media.

Those celebrities who have, in unguarded moments, endorsed Powell’s views have been instantly subjected to vehement criticism. Such unlucky individuals have included rockers Eric Clapton (remarks made while drunk in 1976), and Morrissey, who in a 2007 newspaper interview did not explicitly mention Powell, but made remarks critical of immigration.

Christopher Priest’s ‘Fugue for a Darkening Island’ (first published in 1972; this Pan Books paperback, 125 pp, was issued in 1978, with cover art by Mike Ploog) takes the Enoch Powell controversy and places it in a near-future (i.e., late 70s) England.

The first-person narrator is one Alan Whitman; white, British, five feet and eleven inches tall, of middle-class background. He is witness to the arrival in the UK of an exodus of African refugees, fleeing the aftermath of a limited nuclear war in Africa. As a stream of ships crammed with half-starved, injured, penniless refugees descend on Britain, the government is wracked by internal disagreement over whether to observe human rights conventions and provide food, shelter, and residency to the refugees, or to prevent the ships from disembarking and forever altering the demographics of the UK.

As the novel opens, the exodus has led to the arrival of 2 million Africans, or ‘Afrims’. The government is in disarray, the crisis having splintered the ruling class into a number of factions, each fielding a private militia to harden their grasp of power. The country’s economy has collapsed, along with law and order, as large numbers of Africans occupy metropolitan areas and outlying towns and villages, aided in some cases by white liberals and British communists.

The novel follows the travails of Alan Whitman as he and his family flee their comfortable suburban house in a poorly planned journey to possible refuge in the coastal regions of northern England. Their travels will take them through a landscape marked by violence between armed bands of raiders, government factions, and Afrims……a landscape with decreasing hope of sanctuary……

‘Fugue’ would seem to have a premise tailor-made for the sort of engaging, apocalyptic adventure that characterizes The Death of Grass, or The Day of the Triffids. Unfortunately, ‘Fugue’ is a disappointment.

Most of this is due to the fact that, as a novel written in the heyday of the New Wave era, author Priest chose to use an ‘experimental’ prose structure in which the text is not divided by chapters. Instead, he provides paragraphs separated by ellipses.

To further lend the novel an avant-garde flavor, the overall narrative is discontinuous, with each paragraph representing a narrative thread different in time and space. Accordingly, one paragraph may occupy itself with a moment from Whitman's college years, followed by a paragraph describing a present-tense event, followed by a paragraph detailing an event just prior to the arrival of the Afrims.

Much of the narrative takes place in the time before the Afrim arrival and is concerned with reminiscences of Whitman’s sexual experiences and marital problems, another trope dear to the New Wave movement.

As a consequence of the discontinuous narrative, whenever the author builds up some degree of suspense, it is dissipated as the succeeding paragraphs shifts the reader to some locale distant in time and space.

It also doesn’t help that the story’s protagonist is one of the more inept in apocalypse fiction: Alan Whitman is vacillating and weak. Perhaps not intentionally, Priests’ depiction of Whitman as a white liberal means that Whitman’s actions are marked by constant indecision and self-doubt.

I finished ‘Fugue’ thinking it an improvement over its French counterpart, Jean Raspail’s The Camp of the Saints (1973), in which an armada of decrepit ships, packed with diseased, starving Hindus, inexorably sails for the southern coast of France, while the French government dithers over whether or not to accept them.

But it’s safe to say that neither 'Fugue' nor 'Camp' really succeeds as an entertaining example of near-future social apocalypse.

2 / 5 Stars

Most Americans are unfamiliar with John Enoch Powell (1912 – 1998), a conservative British politician who in 1968 made a speech in which he predicted that immigration into the UK ultimately would lead to racial violence, as the native population found itself overwhelmed by the social and economic problems attendant to an influx of foreigners to a small territory.

The so-called ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech was denounced by the UK political establishment and the national media, and Powell was removed as a member of the Heath government. His name soon was promoted by the media and British intellectuals as synonymous with an element of UK society that embraced racism and bigotry.

Powell’s declaration touched a nerve among the working- and middle- class British population, however, and his attitudes towards immigration and cultural assimilation became subsumed into the larger issue of whether the British Isles had sufficient ecological capacity to support a large population. During the 70s, on into today, the increases in crime, crowding, depletion of the welfare system, and other social strains associated with immigration, maintained the middle class's sympathy for Powell’s stance.

As 2014 begins the UK Independence Party (UKIP), which calls for strict controls on immigration and the deportation of foreign-born criminals, has garnered unprecedented support at the polls, something which has greatly disturbed PM David Cameron and the Conservative party, the British political establishment, and the media.

Those celebrities who have, in unguarded moments, endorsed Powell’s views have been instantly subjected to vehement criticism. Such unlucky individuals have included rockers Eric Clapton (remarks made while drunk in 1976), and Morrissey, who in a 2007 newspaper interview did not explicitly mention Powell, but made remarks critical of immigration.

Christopher Priest’s ‘Fugue for a Darkening Island’ (first published in 1972; this Pan Books paperback, 125 pp, was issued in 1978, with cover art by Mike Ploog) takes the Enoch Powell controversy and places it in a near-future (i.e., late 70s) England.

The first-person narrator is one Alan Whitman; white, British, five feet and eleven inches tall, of middle-class background. He is witness to the arrival in the UK of an exodus of African refugees, fleeing the aftermath of a limited nuclear war in Africa. As a stream of ships crammed with half-starved, injured, penniless refugees descend on Britain, the government is wracked by internal disagreement over whether to observe human rights conventions and provide food, shelter, and residency to the refugees, or to prevent the ships from disembarking and forever altering the demographics of the UK.

As the novel opens, the exodus has led to the arrival of 2 million Africans, or ‘Afrims’. The government is in disarray, the crisis having splintered the ruling class into a number of factions, each fielding a private militia to harden their grasp of power. The country’s economy has collapsed, along with law and order, as large numbers of Africans occupy metropolitan areas and outlying towns and villages, aided in some cases by white liberals and British communists.

The novel follows the travails of Alan Whitman as he and his family flee their comfortable suburban house in a poorly planned journey to possible refuge in the coastal regions of northern England. Their travels will take them through a landscape marked by violence between armed bands of raiders, government factions, and Afrims……a landscape with decreasing hope of sanctuary……

‘Fugue’ would seem to have a premise tailor-made for the sort of engaging, apocalyptic adventure that characterizes The Death of Grass, or The Day of the Triffids. Unfortunately, ‘Fugue’ is a disappointment.

Most of this is due to the fact that, as a novel written in the heyday of the New Wave era, author Priest chose to use an ‘experimental’ prose structure in which the text is not divided by chapters. Instead, he provides paragraphs separated by ellipses.

To further lend the novel an avant-garde flavor, the overall narrative is discontinuous, with each paragraph representing a narrative thread different in time and space. Accordingly, one paragraph may occupy itself with a moment from Whitman's college years, followed by a paragraph describing a present-tense event, followed by a paragraph detailing an event just prior to the arrival of the Afrims.

Much of the narrative takes place in the time before the Afrim arrival and is concerned with reminiscences of Whitman’s sexual experiences and marital problems, another trope dear to the New Wave movement.

As a consequence of the discontinuous narrative, whenever the author builds up some degree of suspense, it is dissipated as the succeeding paragraphs shifts the reader to some locale distant in time and space.

It also doesn’t help that the story’s protagonist is one of the more inept in apocalypse fiction: Alan Whitman is vacillating and weak. Perhaps not intentionally, Priests’ depiction of Whitman as a white liberal means that Whitman’s actions are marked by constant indecision and self-doubt.

I finished ‘Fugue’ thinking it an improvement over its French counterpart, Jean Raspail’s The Camp of the Saints (1973), in which an armada of decrepit ships, packed with diseased, starving Hindus, inexorably sails for the southern coast of France, while the French government dithers over whether or not to accept them.

But it’s safe to say that neither 'Fugue' nor 'Camp' really succeeds as an entertaining example of near-future social apocalypse.

Labels:

Fugue for a Darkening Island

Sunday, December 29, 2013

Thursday, December 26, 2013

Steampunk: An Illustrated History

'Steampunk: An Illustrated History' by Brian J. Robb

This chapter also devotes considerable text to the appearance of proto-steampunk in the 1970s, and the prominent role of authors such as Michael Moorcock.

'Steampunk: An Illustrated History' was published in 2012 by Voyageur Press, Minneapolis, a company specializing in books on a variety of eclectic topics.

At 11 inches x 9 3/4 inches this is a heavy, well-made, chunk of a picture book.

Its production values are not just high, but perhaps too high; for example, each page is overlaid with a 'watermark' style graphic designed to impart a fusty, aged appearance reminiscent of a 19th century tome, but this stylization can render the text rather difficult to see.

'Steampunk: An Illustrated History' features a Forward by James P. Blaylock, one of the founders of the genre. Following an Introduction by author Robb, the book provides 9 chapters that range the genre from its beginnings in 19th century Britain, to the present time .

Chapter 1, 'The GIlded Age', is an overview of 19th and early 20th century sci-fi and fantasy and showcases Verne, Wells, and Burroughs, among others.

Chapter 2, 'From Cyberpunk to Steampunk', primarily is devoted to the three authors who, while attending college in Orange, California in the early 1970s, would come to create the genre known today as Steampunk: Tim Powers, James P. Blaylock, and K. W. Jeter.

Author Robb also devotes some discussion to the interaction of the burgeoning Steampunk movement with the Cyberpunks, as exemplified by the release of The Difference Engine, by Sterling and Gibson, in 1990.

Chapter 3, 'Reinventing the Victorians', covers Steampunk literature during the late 80s on through the 1990s, when, following the efforts of Blaylock, Jeter, and Powers, more authors began to embrace, and expand, the genre.

Here, Robb takes a generous view of what comprises Steampunk, including novels that I would call 'Steam fantasy', or 'New Weird', fiction.

Chapter 4, 'A Young Lady's Primer', deals with the prominent role of female protagonists in Steampunk. This chapter struck me as a contrived effort to present the argument that Steampunk plays some sort of post-modern role in female emancipation. The contents of this chapter probably would've been better utilized by being integrated into the other chapters.

Chapter 5, 'Nitrate Nightmares and Selenium Dreams', focuses on the portrayal of Steampunk in movies and tv. This is a well-written and comprehensive chapter that starts with the efforts of Georges Melies in 1902, through the serials of the 1930s, on up to today.

Chapter 6, 'Clockwork Graphics', looks at Steampunk-themed comic books, graphic novels, and video games. This is another well-organized and informative chapter, with plentiful examples of works spanning the interval from the 1980s up till today.

Chapter 7, 'An Empire Strikes Back', examines the Steampunk movement in Japan, in fiction, comics, and films.

Chapter 8, 'Of Cogs and Corsets', covers the advent of Steampunk as a pop culture phenomenon in the US during the 2000s, a decade which saw Steampunk fashion morph from cosplay unique to sci fi conventions (and other refuges for the socially awkward) to a genuine hipster movement. The chapter also looks at fandom's embrace of Steampunk-inspired music and art.

This aspect of Steampunk has been avidly embraced by people under the age of 40, particularly young singles, as evidenced by events such as the 'Tweed Ride', sponsored by the 'Dandies and Quaintrelles' association, that occurs each Fall in Washington, DC.

The final chapter, 'Back to the Future', covers the recent history of Steampunk as a mainstream phenomenon, which - arguably - came about in May, 2008, when an article about the culture appeared in The New York Times.

Steampunk now has become a dominant force in sf and fantasy publishing, and Robb covers the massive increase in Steampunk novels, comics, films, and television shows that has taken place since 2010.

While this chapter provides a good overview of recent Steampunk, in my opinion, the author shies from the important question to whether much of this output is of good quality, or simply an effort by publishers and editors to exploit the phenomenon.

With Steampunk novels being launched every month by publishers like Angry Robot, Pyr, and Tor, one has to ask: just how much of this material is really worth being put into print ? In my opinion, the economic future of Steampunk publishing risks collapse due to overproduction, and a diminution of quality.

Summing up, 'Steampunk: An Illustrated History' is a very good examination of the genre. While I recognized many of the comics and novels listed in the book, there were quite a few that I was not familiar with, and these seem worth investigating.

Accordingly, I recommend this book not just to Steampunk fans, but to anyone who is a fan of sci fi and fantasy literature.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)